The history of American immigration by Serbs can be divided into two periods: 'early immigration' from 1820, when the immigration of immigrants was introduced, until 1880, and 'later immigration' after 1880.

Emigration for the Serbs was not a question of the economic penetration of other countries but of moving from an overpopulated countryside to the towns, though the often insurmountable obstacles of foreign language and customs hampered transformation from peasant to urban dweller. Generally, immigrants would settle in groups from the same districts, clan or province, which made it easier for them upon arrival to find their first accommodations and employment. Along the same lines, they would set up mutual-aid and cultural societies, though if they came from different places, they would vie for precedence in provincial exclusivity, exaggerating and preserving their distinctive features. In many ways they were very different: some from free Montenegro and a few from Serbia, others from Croatia, still others from Banat and Bačka, from Bosnia and Herzegovina and Macedonia, from the Bay of Kotor and Dalmatia. Their entire life was focused on the limited area between factory or mine and their small community. From this narrow circle of people came ail their comforts and joys of life, but also quarrels and enmity, the only place where personalities and ambitions could take shape, where wounded pride and arrogance found release. Over the years they often came into contact with fewer people than in their old-country villages. If an individual began to climb the social ladder, he could do it only at the expense of his relatives and countrymen, for whom he became a leader and protector, rather like the headman in the village he had left. Immigrants from the Serbia of Prince Miloš Obrenović, even a hundred years after his death, spread across the continent, beneath the cruel fist of big industry and exposed to the single cauldron of Americanization, melting and molding something new.

About this initial period of immigration one can learn most from the stories of the oldest immigrants, from the accounts of different periods and places and from memoirs published in various newspapers. Just before the last war, Jovo Marie from Gary, Indiana began to publish in the American Srbobran a series of articles entitled "Pioneer", actually his autobiography from the day he arrived in the United States. Here one finds the first immigrants walking in apostolic fashion from place to place, taking on whatever work they could find, twenty or so living together bed by bed in shacks and barns where sometimes the companies paid their board. Frequently they did their own cooking, especially if they were living in isolated railway cars. Again and again they changed jobs and places, drawn onward to new factories, where a dozen of them would rent a small wooden house and set up housekeeping, establish their own house rules, a duty roster for cleaning, washing and heating much like an extended family in the Old Country. As soon as they saved up enough money and learned a little English, they would leave these communities, marry the daughters of earlier immigrants, or summon young women from the Old Country, to start their own families.

....They did not like America, nor did America show much interest in them; emigration was simply a matter of money. An average laborer could save 200 dollars a year; the equivalent of 1,000 crowns or perpers, a sum of which few in the Old Country could even dream.

Every immigrant represented the rock or soil of his Homeland, but in time he was ground into international sand and dust. Each founded a dynasty but lived within his own shadow, which grew ever smaller until vanishing into oblivion. Every immigrant represents some personal sorrow and drama as he resists his fate, striving to preserve his name and language, age-old customs, and organize his new life as before.[1]

Stevan Karamata, Director of the Serbian Bank in Budapest, who visited the United States in 1910, gave a similar description of immigrant life. Questioned about the statistics of certain Serbian centers in North America, in his Report to Serbian Patriarch Lukijan, among other matters, he also said:

Wherever our people live, they are mostly concentrated in one place, and this is also the case with immigrants from other countries, so that in each place each nationality gathers and stays in a group.

Our people live miserably, do the hardest labor in factories, mines and railways, in the forests. Almost everywhere their work is dangerous to life and health, and not a day passes without several men being injured. At home they would never dream of doing such work. Wages vary, depending on the job and skill, from 1.30 to four or five dollars, but most earn about 1.50 to two dollars a day, and work 11 hours a day. Life in America, however, is very expensive. They live in so-called boarding houses, which one married person rents and provides room and board for 20-30 people, who live there in very unsanitary conditions. Their diet consists usually of roast meat... Among the Serbs, Montenegrins live most miserably, saving even on food, so that many ruin their health, and a large amount of what they save is spent afterwards on costly train fares, as they look for easier work. The soberest are the Herzegovinians, who live in moderation.

In most places there are few educated people, usually clever or literate peasants, former laborers, who have invested their savings in some undertaking, usually a saloon, or some kind of store (groceries, clothing, meat, bread) and cater to our people.

More than half of our immigrants are illiterate, and, not knowing English, are cheated all the time, usually by our own swindlers and ne'er-do-wells, who are numerous.[2]

Everyone who has written about the immigration of the Serbs to America generally takes 1880 as the year when Serbs began to immigrate in large numbers. However, the history of Serbian emigration to the North American continent must be divided into five periods, i.e. groups of immigrants: the first group belonging to the 'early immigration' from 1815 to 1880; the second and largest group belonging to the 'later immigration' from 1880 to 1914; the third group between the two world wars, 1918-1941; the fourth group from Western Europe, 1945-1965; and the fifth group of immigrants from Yugoslavia from 1965 until the present day.[3]

All accounts of the Serbs who emigrated to America invariably claim that the first Serb known to have come to America (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) in 1815 was Đorde Šagić, born in Hungary, also known as Đorde Fisher. Vasa Stajić, however, discovered that Jovan Mišković "around 1740 spent five years in America,"[4] which means that the first Serb came to America much earlier than Šagić. More data about the Serbs in America during that period are also to be found in Podunavka (1848).

During this period Serbs settled in New Orleans, along the Mississippi delta, in California, Nevada and Arizona. In 1841 Serbian immigrants in New Orleans formed a Greek parish together with Greeks and Syrians, while immigrants in San Francisco founded a Greek-Russian parish with Greeks and Russians.[5]

The largest numbers of Serbs to settle in America between 1880 and 1914 originated from Herzegovina, the Bay of Kotor, Dalmatia, Slavonia, Lika, Banija, Kordun, Bosnia and Vojvodina, with the least coming from Serbia. According to American statistics, 650,545 South Slavs, including 142,441 Serbs and Bulgarians, immigrated to America during this period. Sometimes the American administration classified Serbs emigrating from Austro-Hungary simply as subjects of that country, and not as Serbs.

Hungarian state statistics in annual reports from the beginning of this century show that, in fact, "especially Orthodox [i.e. Serbs and Romanians] declined sharply in population numbers, particularly in the towns."6 "From parts of extensive, fertile Hungary... spontaneously emigrated large numbers of the non¬ Hungarian population, who left the fertile plains of Backa and Banat and emigrated to far-off America." Statisticians claim that this happened "due to the overpopulation of Backa"! - for Backa "suffers from overpopulation," as they said.[7] But if Backa and Banat were, in fact, 'overpopulated' and no longer able to nourish their indigenous population, why did non-Hungarian, and only non-Hungarian settlers disappear 'spontaneously' from these 'overpopulated' regions!?

This particular phenomenon was actually a matter of coveting traces of Hungarian 'compulsory, silent, internal colonization,' which drove the autochthonous population from their homes and from the most fertile lands under the guise of overpopulation, sending them abroad to make room for newcomers from northern Hungary. Hungarian statesmen, Count Tisza especially, demonstrated great skill with respect to internal colonization and for this purpose generously subsidized from the State Treasury, for example, the Cunard Shipping Line, which received premiums for emigrants - naturally not Hungarians (who were not granted emigration visas) - Serbs, Romanians, Slovaks and Germans. The Hungarian administration showed particular skill in implementing this plan; it was therefore extremely important for the Hungarian State to have an well-organized administration.[8] This administration helped ensure that precisely from fertile Backa "over 124,000 and from Banat 52,000 souls, mostly Serbs, emigrated to America with the aid of the privileged Cunard Shipping Line. Altogether 175,000 souls, who could not nourish themselves in bounteous Vojvodina!"[9] During this same period 44,233 persons returned to their original homes. In 1897 when an agent appeared in Slavonia to recruit Serbs for America, Miron, Bishop of Pakrac (1890-1941) wrote a circular letter to his priests, adjuring them to preserve the people from unnecessary re-settlement.

In addition to the above-mentioned, there were other reasons and motives for emigration.

Namely, in a nationally mixed milieu the Serbs suffered and were persecuted because of their affiliation with the Serbian Orthodox Church. There were even court trials, such as the one for high treason in Zagreb when distinguished Serbs were tried and often even interned. Young Serbs, fleeing three years of military service in the Austro-Hungarian army, immigrated to America and thus avoided conscription. Potential emigrants received invitation from relatives who had gone to America earlier, as well as gifts and money for the fare. The American State Immigration Office reports that in 25% of the cases travel expenses were paid for by earlier immigrants.[10]

When the first immigrants set foot on American soil, they found a completely different situation from what they had left at home. Here there was no political unrest, or persecution or harassment, or compulsory military service, or social disparagement or identity cards or reporting every change of address to the police. They found a completely different way of live with the accent on liberty. True, they had problems because they did not know American English, American customs and institutions. Their education consisted of two to four years of elementary schooling. According to an Immigration Office estimate, 40% were illiterate. They lacked job experience. Yet in America they found an opportunity for good jobs. American industrial expansion had a need for cheap unskilled labor, and the immigrants wanted to work. They soon found jobs in foundries, iron mills, coal and copper mines and in various kinds of construction work. Many were office workers, who preferred to reside in places where there were other Serbs. The rooms in the boarding houses were full of beds. Sometimes two boarders in the same room, working two shifts, slept in the same bed. A lot of these accommodations were barracks providing board and lodging to large numbers of laborers.[11]

Many of the first immigrants, after they had made good in America, decided to stay. True, a large percentage were illiterate, but they were often the ones who best preserved their faith and Serbian nationality. They also sent more than 8,000 Volunteers during the First World War for the liberation of Serbia, kept their children in the faith and Serbian spirit and taught them the Serbian language and Serbian folk poetry. Not a single case is known of any one of them being in an American jail. As soon as they purchased a small house, and sometimes even before, they brought over their families, or Serbian girls were sent by their parents, and with these brides in the New World they started families, which were often quite large.

In 1874, even before establishing church-school congregations, the Serbs founded, often together with the Croats, charity societies to provide assistance in times of trouble or accidents. Eventually, many of these societies united into two federations, and then into a single Serb National Federation with its seat in Pittsburgh. In addition to these societies, for their young people the Serbs founded Sokol [Eagle] athletic organizations, choirs, tamburitza orchestras and youth clubs.

Since most of them were peasants, mainly from Serbian regions then part of Austro-Hungary or from Montenegro - and like peasants spiritually close to the Church and religious rites and customs - after leaving their Homeland they could not also abandon all the spiritual characteristic they had brought from their Homeland. On the contrary, physical separation made them spiritually closer. As a contributing circumstance they were simple, poor people without close spiritual contact with real Americans, with the foreign world around them. Like other Slav immigrants, they were an island in the great ocean of a race that resembled them little in culture and way of life. Living in isolation, constantly pining for their Homeland, idealized because of the distance and their arduous life, it was natural that they remained foreigners among foreigners, that they should want to have their own priest as a spiritual leader and interpreter of Homeland ideals.[12]

The first American to become an Orthodox priest was born in 1863 in a Serbian family named Dabović which had immigrated to America from the Bay of Kotor in 1894. Jovan John Dabović (Dabovich) later Sebastian, was to build the first Serbian Orthodox church in America - the Church of Saint Sava in Jackson, California - and was the first to head the newly founded Serbian Religious Mission in America, which was part of the Russian Orthodox Church.

The first Serbian immigrants in America also showed their patriotism during the First World War. As Nikolaj, Bishop of Ochrid was to say:

Patriotism is such a powerful feeling among them, even stronger than religion... The former wartime Volunteers are especially held in esteem. Immediately following them are those who gave their hard-earned dollars to the Serbian Red Cross or for the orphans. I must immediately add that they truly sacrificed a great deal, considering their pain and poverty. If one considers the sacrifice just in money - leaving blood aside - then the Serbs in America sacrificed more, comparatively speaking, than any other part of our country. No matter who collected the money, or when it was collected, they always gave. Those who didn't have it, borrowed it humbly and gave - wanting to do no less than their brothers, wanting to help their brothers.[13]

In 1915, hoping to acquaint the Western world with the sufferings of the Serbian people, the Serbian government sent to America Hieromonk Dr. Nikolaj (Velimirović), who delivered several lectures in various parts of the United States. Thanks to him, and to Mihajlo Pupin and the Serbian priests in America, many Serbs from America went by way of Greece as Volunteers to help Serbia, despite ihreats from the Austrian Legation in Washington, which had launched a vigorous propaganda campaign against the Serbs' departure for the front. The Ban [Governor] from Zagreb,

on December 9, 1914 wrote a private letter to Count Tisza, warning him of activity among the immigrants and informing him that he already knew quite a bit about the matter and felt that this political agitation was not insignificant. In November the Ban had been doing his utmost to stop the movement, by means of the press in America. In other words, the government tried to bribe the press into counter-agitation; thus the Ban reported that the American Narodni List [National Paper] was writing and working in the interests of the monarchy according to instructions from the Croatian government, while all the other papers, both Serbian and Croatian, were completely against the monarchy; the Ban also ordered his agents to take counter-action.[14]

Through its diplomatic representatives in America, Austro-Hungary kept a close eye on the activities of its former subjects.

But how prompt the Austrian Consular Service actually was, can be seen from a letter from Austrian Consul Ernest Ludwig, who on February 16, 1914 from Cleveland, Ohio replied to an order dated January 5, 1913, reporting to his chief about Pupin's political agitation in America. Consular Reports, on conditions among our people and their work in America before and during the war are quite significant since they ret1ect the feelings of our people in the former monarchy, which through the actions of its authorities had compelled them to seek a living abroad. These Reports caused the Viennese Minister of Foreign Affairs to request that the Croatian Ban intervene among the immigrants in America; in 1913 he tried with money to win over the main immigrant leaders, who through the press could int1uence people not to express their discontent with the monarchy. But only two papers, including the above mentioned Narodni List [National Paper], took the bait and wrote in favor of the monarchy. All the rest, both Serbian and Croatian, followed the same path, the same spirit of unity, seeking union of the South Slavs. That year the Croatian government published a brochure by Stjepan Radić who, as leader of the Croatian Peasant Party and an opposition deputy in the Croatian Assembly, addressed the Croats, the Austrian emperor and monarchy. 'This booklet does not exist among copies obligatory given to the University Library in Zagreb. During the war it was not discarded whereas many Serbian books were banned and removed from the shelves. Only from Radić's article in his Dom [House] can one see that he did write the brochure and in what vein of thought it was written.[15]

By some estimates there were 200,000 Serbs in America by the time of the First World War. According to the US Census of 1910, as cited by Pero Slepčević, there were a total of 3,024,323 Slav inhabitants, including 26,752 Serbs, 3,961 Montenegrins and 35,195 undetermined Slavs.[16] Pero Slepčević continues that official American statistics as regards Serbs were less reliable

than the number of Yugoslavs in general. First of all, this is because of the ridiculous division into [categories such as] "Croats and Slovenians," "Dalmatians, Bosnians and Herzegovinians," and "Bulgarians, Serbs and Montenegrins." Sometimes by Serbs they mean only Serbians (inhabitants of Serbia proper) and sometimes others. Finally, not even our own people were sufficiently aware to declare their name, or even their language, let alone their nationality.[17]

According to official American statistics concerning religion and published in 1915, in America there were "64,000 Serbian Orthodox." This number, indicates Slepčević, may be "considered to be the lowest possible number reflecting the number of Serbian immigrants in America."[18]

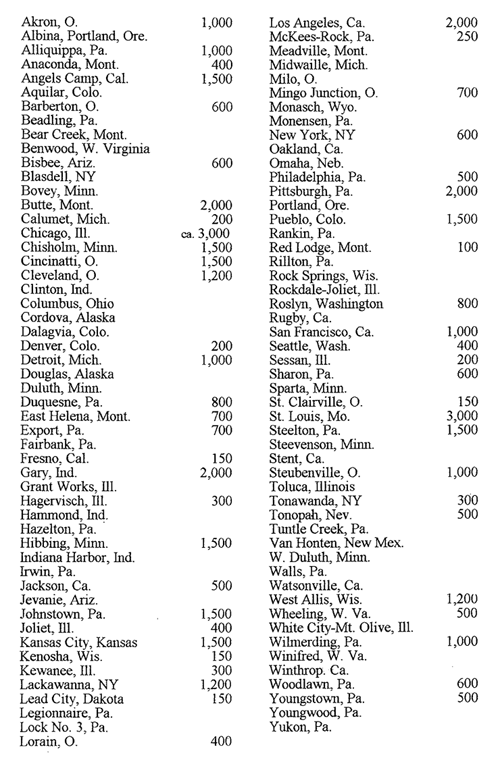

Stevan Karamata provided the following list of "Serbian colonies" in the United States, and indicated the number of Serbian inhabitants in each location:[19]

Furthermore, according to Karamata:

For places where the number of Serbian inhabitants is not indicated, I was unable to find out the approximate number of Serbs living in these places, while the figures noted for some places are not accurate, only approximate. In addition to the places listed above, our people live in many other towns that I was not able to locate during my brief visit to America. The total number of Serbs in the United States is considered to be from 150,000 to 200,000 souls, who originate from all Serbian regions except the Kingdom of Serbia, from which there are only a few individuals, mostly craftsmen, merchants and former civil servants, but there are absolutely no peasant emigrants.[20]

Although the above-mentioned number of Serbs is only approximate, this Report by Stevan Karamata is valuable for us. He was the first and so far the only person to list all the places where he found Serbian inhabitants, so that anyone who wishes to study Serbian migration in America must begin with this list, the most complete at the time. When compiling the above list, Karamata did not use the findings of the government census, as yet incomplete, and as far as the Serbs were concerned, unreliable, as Pero Slepčević, who used the data, remarked. Karamata suspected something like this when he said:

Government statistics according to nationality do not exist at present. Early this year a census was taken according to nationality, but this has not yet been published and prepared for printing. When it appears, I will procure it and take the figures from it, but it is already known that the data for us will not be accurate, since many of our people registered as Croats, Austrians and Hungarians, according to the provinces they came from.[21]

Not even the exact number of Serbian Volunteers who joined the Serbian and Montenegrin armies during the First World War has been yet determined. The figure ranges from 8,000 to 13,000. Nor is it known how many were killed or drowned en route from America and Canada. In any case, these patriots deserve to have a comprehensive study written about them.

Interest in immigrating to America continued after the First World War. However, in 1921 the US Congress set a quota limiting the number of people who could immigrate to America. In this way, the number of Serbian immigrants was drastically reduced.

With the creation of the Kingdom of the Serbs, Croats and Slovenes many lost their desire to emigrate, especially when the United States was hit by the Depression, during which many Serbs lost their jobs. Owing to the Depression a certain number of Serbs returned to Yugoslavia from America.

Unfortunately, not even the Serbian Orthodox Church in America and Canada ever managed to make a count of our people, and if it had tried, it would have met the same fate as the American government census. First of all, the Serbs did not live only in places where there were organized church-school congregations, but wherever they found employment. Second, from the earliest times, even after the first church congregations were founded, not all Serbs joined. Some were members, paid their dues (parish tithes) and were in good standing with the congregation and parish church and as such enjoyed the privileges accruing to them on the basis of congregation by-laws. Some Serbs only had the status of parishioner and their exact number was never known, since they addressed the parish priest only in cases when they needed some service. The exact number could not be established even on the basis of telephone books because some Americanized their last names, like one of the first Serbian immigrants - Đorđe Šagić - who changed his name to Fisher.

It is important to note that in later censuses taken by the American government many Serbs registered as Americans, even though they felt they were Serbs and participated in the activities of their parishes and congregations, assuming important positions in them. When serving in American public life they often did honor to the nation from which they originated and to which they belonged spiritually.

---

[1] Božidar Purić, Biografija Bože Rankovića, Munich, 1963:30-32.

[2] Stevan Karamata, "Report to the Patriarch Lukijan, Budapest, October 27, 1910", State Archive of the Secretariat of Foreign Affairs, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Kingdom of Serbia, 1910, F.II, I/11:378-380.

[3] Dr. Michael B. Petrovich, "How Many Serbs in America? Some Statistical Problems", [ms.]:2.

[4] V. Stajić, "Novi podaci o Zahariju Orfelinu" [New Data about Zaharij Orfelin], Glasnik istorijiskog društva [Historical Society Gazette] VIII, Novi Sad, 1935:127.

[5] Orthodox America, Syosset, New York, 1975:33.

[6] Dr. Vladimir Margan, "Pomadjarivanje u bivšoj Ugarskoj" [Magyarization in Former Hungary], Glasnik istorijiskog društva [Historical Society Gazette] VIII, Novi Sad, 1935:143.

[7] Ibid., 144.

[8] Ibid., 145.

[9] Ibid., 146.

[10] Dr. Milan G. Popovich, "Immigration of the Serbs in America", The Serbian Orthodox Church through 750 Years, Cleveland, Ohio, 1969:27.

[11] Ibid., 29.

[12] Nikolaj, Bishop of Ochrid, "Report to the Holy Assembly of Bishops about the Conditions and Needs of the Serbian Orthodox Church in America, Sremski Karlovci, August 26, 1921", Archive of the Holy Hierarchic Synod, without number, dated August 13/26, 1921.

[13] "Serbian Church-School Congregation of Saint Sava Cathedral in Milwaukee: Brief History", Dedication of St. Sava Serbian Orthodox Cathedral, Milwaukee, 1958:9.

[14] Dr. Đuro Surmin, "Austrijske vlasti i naši iz Amerike", [Austrian Authorities and Our /People/ from America], Contribution Concerning the Attitude of the People toward the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, Narodna odbrana, Belgrade, 1934:432.

[15] Ibid., 433.

[16] Pero Slepčević, Srbi u Americi [Serbs in America], Geneva, 1917:7.

[17] Ibid., 15.

[18] Ibid., 15-16.

[19] Karamata, op cit., 341-342.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ibid., 378.

From the book History of the Serbian Orthodox Church in America and Canada 1891-1941 by Bishop Sava of Šumadija